Just another bioinf blog

Blog by Michael Roach: @BeardyMcJohnFace@genomic.social

email: mroach@bioinf.cc

Chardonnay Part 1: The Reference Genome

19 May 2020

Chardonnay was the second grapevine genome to be assembled using third-generation long read sequencing. Like the Cabernet Sauvignon genome, FALCON-Unzip was used to generate a 'diploid' assembly. The assembler, sequencing technology, and the concept of diploid assemblies were relatively new at the time so there were several hurdles to overcome before the Chardonnay reference genome was ready for our clonal marker work.Continued in Chardonnay Part 2: Clonal Marker Discovery, Read the paper

This project began well before I started at the AWRI, with the original approach using pool-BAC sequencing. The high heterozygosity and repeat-content of grapevine genomes had been identified as a potential problem for assembly. The pool-BAC strategy was intended to alleviate this by reducing the chances of misjoins from repetitive content etc. There were ~100 pools of ~100 BACs being separately sequenced and assembled, and contigs from all assembled BAC-pools would then be stitched together into one final assembly. Unfortunately, we only later learned that there would still be far too many chimeric contigs for it to work properly. My job as a casual was to manually stitch together these contigs using SeqMan Pro, but this went nowhere fast. We eventually bit the bullet and got 56 SMRT cells of RS-II PacBio sequencing, and I started a post-doc. Many people helped us source appropriate compute resources for the assembly. We managed to get a some space on Nectar Cloud for testing the assembler, and access to a 60-core, 900 GB RAM server through QCIF for the actual assembly. A month later we had a draft diploid assembly for Chardonnay!

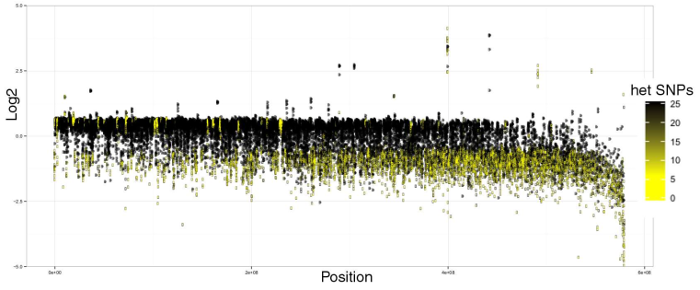

We encountered a problem that seemed to be especially problematic with these third-gen seq based assemblies. Some areas in the genome exhibit very high levels of heterozygosity. This results in contigs from both chromosome copies for these regions being assembled separately, rather than collapsed together and later phased by FALCON-Unzip. The resulting duplication in the final assembly is especially problematic when performing a traditional read-mapping and SNP/InDel calling analysis. Below is the first graph we made to visualize the problem.

Mapping to Chardonnay draft primary contigs. Log2(coverage / mean coverage) over 100 kb genome windows, coloured by heterozygous SNP density.

Mapping to Chardonnay draft primary contigs. Log2(coverage / mean coverage) over 100 kb genome windows, coloured by heterozygous SNP density.

The read mapping for a large portion of the genome is at half coverage as the reads are split between the duplicated contigs. The genome is well over-sized and it’s impossible to call all heterozygous SNPs. We produced the pipeline Purge Haplotigs (which will feature in a future post) to address this issue. Essentially, the pipeline works out which contig pairs are allelic and sorts them into the primary and alternate assemblies accordingly. This ensures that reads from the same region are mapping to the same contigs.

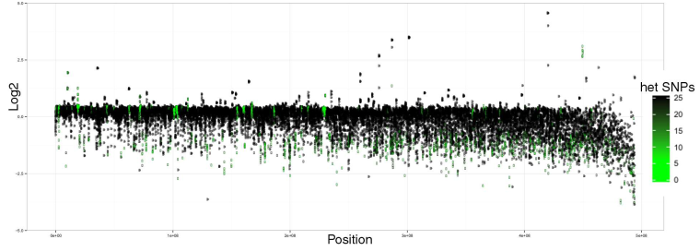

Mapping to Chardonnay Purge Haplotigs-processed primary contigs. Log2(coverage / mean coverage) over 100 kb genome windows, coloured by heterozygous SNP density.

Mapping to Chardonnay Purge Haplotigs-processed primary contigs. Log2(coverage / mean coverage) over 100 kb genome windows, coloured by heterozygous SNP density.

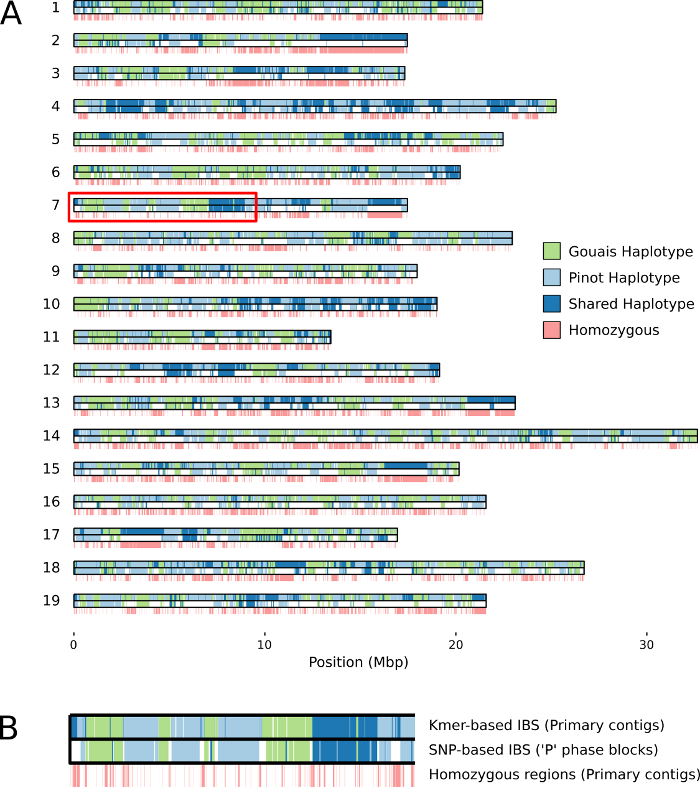

De-duplication is essential for capturing all heterozygous variants within a genome, either through variant calling or direct alignment of the primary and alternate assemblies. On a side note, many diploid assemblies have recently been generated for grapevine cultivars but this de-duplication step has not always been performed (caveat emptor). De-duplication was also essential for identifying the parental origins accross both the primary and alternate assemblies. We used two different approaches; the first was a SNP-based Identity-by-State (IBS) approach on the most contiguous ‘phase blocks’ and the second, a kmer-based approach on the whole primary assembly.

SNP- and kmer-based IBS.

A) Ideogram of Chardonnay primary assembly comparing kmer- and SNP-based IBS calls.

B) enlargement of section indicated in red. Figure from Roach et al. (2018)

SNP- and kmer-based IBS.

A) Ideogram of Chardonnay primary assembly comparing kmer- and SNP-based IBS calls.

B) enlargement of section indicated in red. Figure from Roach et al. (2018)

When we originally tried this with sequencing data for only one of Chardonnay’s parents (Pinot noir) we found that large portions of the genome matched Pinot noir for both haplotypes. Many of these regions were heterozygous which ruled out gene conversion as the source. We suspected inbreeding, but had to sequence Chardonnay’s other parent (Gouais blanc) to know for sure. We were able to not only map out the parental contributions over both haplomes, but also confirm that Chardonnay’s parents are indeed related.

Finally, using the Chardonnay reference genome we were able to find clonal markers for a panel of Chardonnay clones. This was almost an entire project by itself and will be the subject of a future post.

References

MJ Roach, DL Johnson, J Bohlmann, HJJ van Vuuren, SJM Jones, IS Pretorius, SA Schmidt, AR Borneman, (2018), Population sequencing reveals clonal diversity and ancestral inbreeding in the grapevine cultivar Chardonnay, PLoS genetics 14 (11), e1007807 | DOI