Just another bioinf blog

Blog by Michael Roach: @BeardyMcJohnFace@genomic.social

email: mroach@bioinf.cc

Chardonnay Part 2: Clonal Marker Discovery

26 May 2020

The second part of this project involved the identification of SNP and InDel markers that can distinguish the different clones of Chardonnay. The biggest challenge for this aspect was filtering out the hundreds of thousands of false-positive markers, from the millions of heterozygous variants, to identify the few thousand true marker SNPs and InDels.Continued from Chardonnay Part 1: The Reference Genome, Read the paper

The search for clonal markers in grapevine cultivars is not a unique concept. Many groups have tried this in the past using SSR markers but were generally only able to place a large number of clones into a small number of genotype bins. More recent papers attempted this type of work with WGS sequencing data but could only validate a handful of markers due to insufficient coverage and filtering.

Earlier works on SSR markers have identified three and even four genotypes at some marker loci. This happens because the grapevine apical meristem is comprised of at least two genetically distinct cell layers and new mutations only propagate through one cell layer. This is the main reason why identifying these markers is so challenging using WGS sequencing data.

Coverage requirements

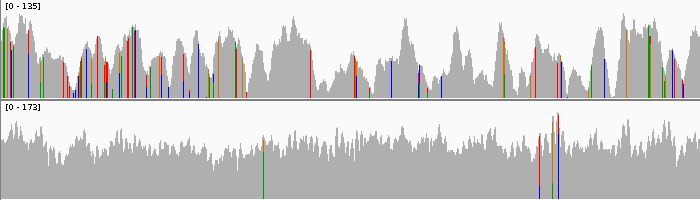

The allele frequency for these markers is low—up to 25 % assuming two cell layers and even representation of each layer. The cell layers might not be evenly represented in the sequencing data and coverage accross the genome can vary as well. Identifying clonal markers depends on reliably calling the absence of a marker for any given sample, which is impossible with insufficient coverage. For Chardonnay, we had to re-sequence an entire batch of samples as the coverage was too low and exhibited bad “saw-toothing”. We estimate > 50-fold coverage is required, but even with deep sequencing, filtering out false-positive markers is difficult.

Example of sawtoothed coverage (top) and normal coverage (bottom)

All-but-one errors

There are many sources of false-positives but this was the most prevalent. Heterozygous variants were called for each of the clone samples and differing calls between them were identified. The majority of these potential marker mutations appeared to be present in all but one or a few samples. These were all false-positives.

No matter what threshold is set for filtering variant calls (p-value/coverage/supporting reads/etc.) there are always samples sitting just above and below these thresholds. We tried multiple variant callers (even GATK and its score recalibration voodoo magic) and it made no difference. Even if only 1:1000 variants are affected, the fasle-positives will still greatly outnumber the true marker mutations. We implemented a kind of ‘fuzzy’ threshold, where the minimum thresholds for any one sample was lenient, but the average across all samples was relatively stringent.

Mapping artefacts

Small differences in insert size, read-length etc. affects how the reads map to the genome. Even if only a small fraction of the heterozygous variants are affected by mapping artefacts, the result is still lots of false-positives. As such, a mapping-independent approach to filtering was required.

We settled on a kmer-based filtering method. Essentially, the novel kmers that arise from a marker mutation are checked to see if they’re present in the raw sequencing data for every sample. If the presence of these marker kmers is not consistent with the marker variant calls then the marker variant is filtered.

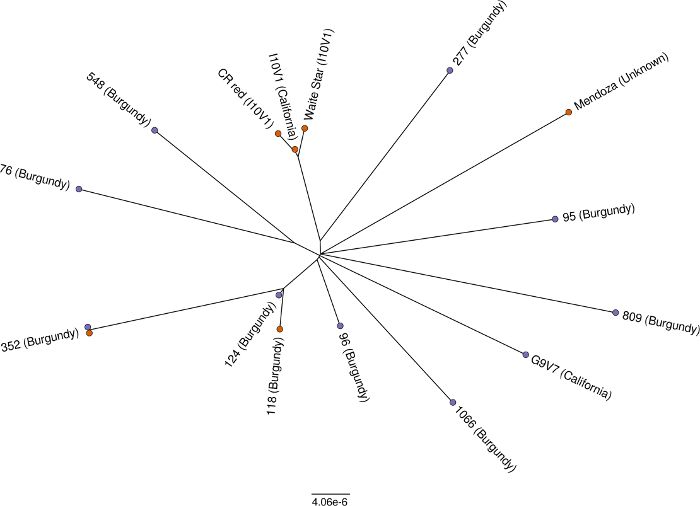

Chardonnay clone phylogeny

The true value in this work lies in being able to genetically differentiate clones and identify shared heritages. Most of the clones had very few shared markers as you can see in the phylogeny below. Clone 352 was sequenced over both sequencing batches and shared 100% of their markers, which was a good sanity check. Furthermore, the relationship between I10V1 and its bud-sports (CR Red and Waite Star) is clear as day. Reliable and accurate genetic testing of grapevine clonal material is a matter of when, not if.

Phylogeny of Chardonnay clones. Figure from Roach et al. (2018)

References

MJ Roach, DL Johnson, J Bohlmann, HJJ van Vuuren, SJM Jones, IS Pretorius, SA Schmidt, AR Borneman, (2018), Population sequencing reveals clonal diversity and ancestral inbreeding in the grapevine cultivar Chardonnay, PLoS genetics 14 (11), e1007807 | DOI